Can you recall a time when you knew Aristotle’s name, but you didn’t really know why he was important? Do your students know, or care, about Aristotle?

I don’t remember the first time I heard the name “Aristotle.” It was probably in an elementary or middle school ancient history unit. But certainly, when it came time for the purchase of my undergraduate philosophy 101 textbooks and Nicomachean Ethics was on the list, I didn’t have any idea why I was reading a document over 2000 years old with an unpronounceable title from halfway around the world.

Transition sentence here.

Yet my professor, like I and my colleagues decades later and states away, made the presumption that an introduction to Aristotle was not necessary for appreciating the authority of his words.

Yet my professor, like I and my colleagues decades later and states away, made the presumption that an introduction to Aristotle was not necessary for appreciating the authority of his words.

Another sentence here.

Aristotle as Rhetorician

When we teach writing, we often begin our discussion of rhetorical appeals with a discussion of Aristotle’s rhetoric. We provide quotes from Aristotle’s On Rhetoric, such as:

“We believe good people more fully and more readily than others; this is true generally whatever the question is, and absolutely true where exact certainty is impossible and opinions are divided.”

We use this quote to demonstrate ethos, the appeal to the speaker or writer’s character, experience, and values. In this particular quote, Aristotle is pointing out that a speaker’s good character appeals strongly to our sense of credibility and helps us to trust the rest of the information provided by the speaker; we are less likely to believe a speaker of ill repute.

But what is the repute of Aristotle? In taking for granted the centuries-old teaching tradition that uses Aristotelian ethics, we forget to address the meta-ethotic appeal inherent in our pedagogy. We take for granted the rhetorical dependence upon which all of our rhetorical grounding is set: the credibility of Aristotle.

We believe that our students will, like us, simply trust that Aristotle has the authority to speak the truth about rhetoric, and in doing so, can lay the foundation for teaching the rhetorical appeals of ethos, pathos, and logos.

Why do we use Aristotle as a starting point? Well, because ethos, pathos, and logos are unfamiliar words outside of rhetorical analysis. The practice of rhetorical analysis dates back at least to ancient Greece, and we have our clearest records of it in works such as Aristotle’s On Rhetoric. It therefore seems to make sense to start our discussion of rhetoric in a writing class by explaining this unfamiliar set of concepts in its historical context.

But how often do we provide the necessary context to establish the historical context of Aristotle’s ethos? Who is Aristotle to our students? Besides some ancient guy that they are told to trust, because they are told to trust us as their teacher or professor.

And so I ask, in terms more familiar for today’s student audience: Does Aristotle have street cred?

Aristotle’s Ancient Authority

Here’s some historical text.

But do we teach this? I’m assuming the answer is no, because that’s been my experience. So if that’s the case, then why not?

Frequency of Aristotle Today

Text

Who are our credible sources

Text

And especially for international students

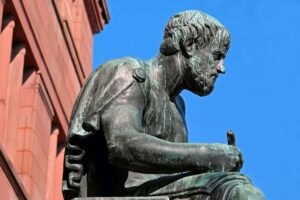

And here he is, Mr. Aristotle himself. I will talk about him more, and then I will be done. That will be the end of my post. I will put all my text here. This is really just a lot of text so that I can continue writing text and it will look like a blog post. More text to fill space. This is really just a lot of text so that I can continue writing text and it will look like a blog post. More text to fill space. This is really just a lot of text so that I can continue writing text and it will look like a blog post. More text to fill space. This is really just a lot of text so that I can continue writing text and it will look like a blog post. More text to fill space. This is really just a lot of text so that I can continue writing text and it will look like a blog post. More text to fill space. This is really just a lot of text so that I can continue writing text and it will look like a blog post. More text to fill space. This is really just a lot of text so that I can continue writing text and it will look like a blog post. More text to fill space. This is really just a lot of text so that I can continue writing text and it will look like a blog post. More text to fill space. This is really just a lot of text so that I can continue writing text and it will look like a blog post. More text to fill space.